Jellies are a rare and beautiful surprise on Catalina Island. They drift past surprised snorkelers in our coves, showing off vibrant colors and graceful tentacles as they float by. Although they are not a regular visitor, Catalina Island boasts a wide diversity of jellies ranging from microscopic hydroids to 12-foot Purple-Striped Jellies.

Purple-Striped Jellies have beautiful colors and possess long oral arms used for catching prey.

Photo credit: Monterey Bay Aquarium

Scientists use the phrase “jellies” instead of “jellyfish” to accurately represent the wide diversity of aquatic floating gelatinous organisms. Unsurprisingly, jellyfish are not actually fish—they lack a backbone and are 95% water. Organisms in the phylum Cnidaria first arrived in the fossil record 714 million years ago and are the first animals to evolve to a multi-organ system. The most famous “true jellies” belong to the class Scyphozoa, meaning that they have a bell-shaped body form for part of their life, possess tentacles or oral arms, and utilize stinging cells for capturing prey. Other gelatinous organisms often mistaken for true jellies include comb jellies (phylum Ctenophora). Although comb jellies look alike to true jellies, have a similar diet, and live in similar habitats they have colloblasts for obtaining food and have rows of cilia that propel them through the water.

CIMI staff and students can see tiny jellies while gazing into microscopes in the Plankton Lab. Small pulsating tentacle buds on a microscopic scale are enough to brighten any curious scientist’s day. Many 2mm species float by during a nighttime snorkel and are only detected with a bright torch. And still, other larger species such as Purple-Striped (Chrysaora colorata), Pacific Sea Nettle (Chrysaora fuscescens), Egg Yolk (Phacellophora camtschatica), and Moon jellies (Aurelia aurita) can be seen on the occasional kayak or near the island’s coastline.

Left to right: Egg Yolk Jelly, Pacific Sea Nettles, and Moon Jellies

Left to right: Egg Yolk Jelly, Pacific Sea Nettles, and Moon Jellies

Photo credit: Alyssa Bjorkquist

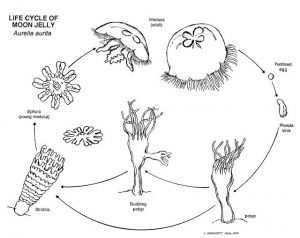

True jellies alternate between different body shapes and lifestyles throughout their short lives. They tend to take on the characteristic free-swimming medusa form as sexually mature adults and settle down as static polyps during development. True jellies are characterized as plankton for most of their lives, meaning that they are weak swimmers and generally drift with the ocean’s currents. Many true jellies migrate vertically in the water column at night by using rudimentary light-sensitive cells to guide them away from the sun. It is very difficult to pinpoint a jelly’s location at any time due to variability in environmental conditions (ocean temperatures, storms, El Niño events, currents/eddies, etc.) and rapidly changing oceanic conditions from global climate change. However, their planktonic lifestyle has them typically puts them in more open waters away from kelp forests or intense surge around rocky coastlines. Good news for our curious snorkelers!

Jellies alternate between static polyps or floating medusa in their short lifecycle.

Photo credit: L. Bornnofft (1995)

Tentacles, oral arms, or a combination thereof are filled with stinging cells called cnematocysts that capture prey and guide it towards the oral opening. Some cnematocysts are powerful enough to register pain when it comes into contact with human skin so it is wise not to touch a jelly, even when it appears dead or washes up onto a beach. (Tip: a vinegar rinse is the medically-recommended way to alleviate a jellyfish sting…not urine. That’s just gross and scientifically incorrect.)

Jellies are critical indicators of environmental health and are an important food source for turtles, some species of fish, and other jellies! Blooms of jellies resulting from pollution runoff and plastic bag presence in the ocean are causing jelly populations to get a bad reputation instead of a graceful example of animal development and hydrodynamic efficiency at a molecular level. Too many jellies in a particular region can shut down boat traffic and create harmful environments for other organisms around them. Furthermore, marine projects researching the effects of ocean pollution are estimating that 83% of sea turtle species worldwide have plastic in their bellies due to their unfortunate physical similarities. Despite their basic appearance, jellies are critical for maintaining an environment’s health and can be a bold sign that something is not how it should be. So next time you see a jelly, wish it good vibes in its eternal drifting life and appreciate their respectful environmental dance from a distance.

Many animals, including sea turtles, confuse jellies for plastic bags and suffer as a result.

Many animals, including sea turtles, confuse jellies for plastic bags and suffer as a result.

Photo credit: Kelly Fong

DIY jelly crafts recycled from plastic and paper:

- Jelly on a stick: http://casahaus.blogspot.com/2010/09/make-your-own-jellyfish-tutorial.html

- Paper bowl jelly: http://www.firstpalette.com/Craft_themes/Animals/paperbowljellyfish/paperbowljellyfish.html

- Plastic bag jelly: http://www.pbs.org/parents/crafts-for-kids/jellyfish-craft/

To learn more about cnidarians and watch them swimming live, visit these online exhibits:

- Monterey Bay Aquarium: https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animal-guide/invertebrates/jellies

Check out this article to learn more about the evolutionary history of jellies: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/04/170410123957.htm

Images:

- Purple-Striped Jelly: https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/-/m/images/animal-guide/invertebrates/purple-striped-jelly-upclose.jpg?bc=white&h=800&mh=916&mw=1222&w=1064&usecustomfunctions=1&cropx=86&cropy=0

- Moon Jelly life cycle: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-Msr4i1jY99k/TrAXAJOhfnI/AAAAAAAAAK8/8qXOkOvkNuU/s640/jelly+life+cycle.JPG

- Plastic bag vs jelly: https://img.haikudeck.com/mg/35207C43-5098-4877-9F0B-C9BBEF99201D.jpg